No Good Deed: Protecting Artists & Entertainers From Liability When Fundraising for Charity

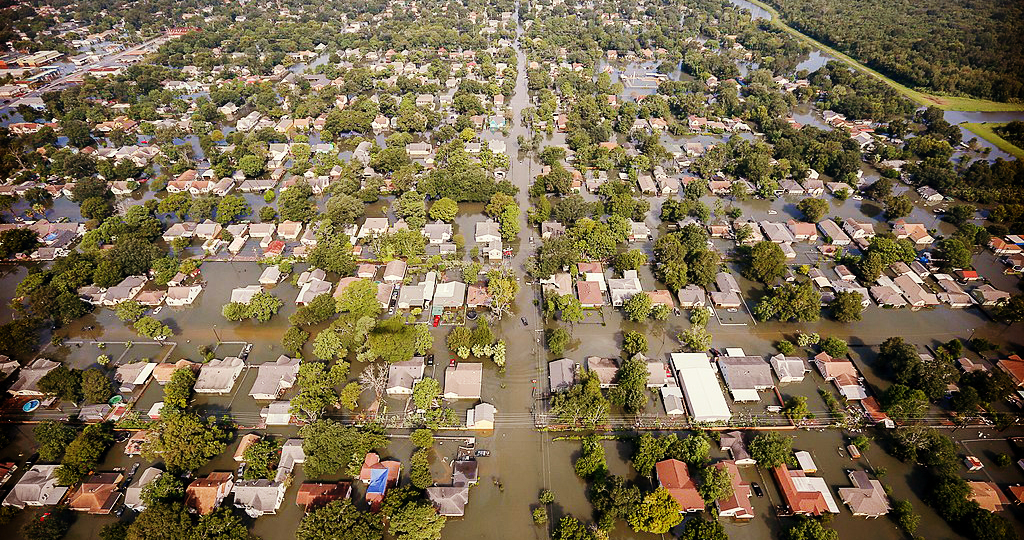

As the heart-wrenching stories continue to pour in from southern Texas, the Florida Keys and most recently, Puerto Rico, one thing is certain… Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria may be no longer, but their wake will surely be felt for years to come. More immediately, in the coming weeks and months, vast amounts of resources, financial aid, and basic life-sustaining necessities will be required to mitigate and rebuild from these unprecedented events. As it does in times of tragedy, the American creative community is once again mobilizing to do its part to help those whose lives have been ravaged by these storms. From star-studded mega-concerts to state-wide initiatives, one way that creatives are heeding the call is by hosting benefit events around the nation to raise funds and/or source items for relief efforts. While there is little doubt that these events derive from well-meaning sentiments, it is still important that event organizers familiarize themselves with, and protect themselves against, potential legal and other pitfalls associated with such events.

In the following paragraphs, we detail a non-exhaustive list of areas of consideration for individuals and small artist collectives looking to host a beneficial fundraising event, but who themselves have no formal designation as a charitable entity. While you are encouraged to read on in more detail below, for those of you looking to jump right to it, the article’s main takeaways can be summed up as follows:

- When deciding on where to host your event, it is often more advantageous to choose an established venue rather than trying to create a ‘pop-up’ space for more than just the obvious reasons. The latter requires the organizer comporting with a host of permitting, insurance, and other requirements which can be arduous and cost-prohibitive.

- Events open to the public are rife with liability. Organizers who undertake fundraising activities outside the protections of a liability-limiting entity such as an LLC or corporation risk being exposed to personal liability for any injury or damage to persons or things. Therefore, heightened consideration should be given to the attendant risks when operating in such a scenario.

- Even if not required, event and other insurance is always a good idea.

- Do not overlook the intellectual property issues attendant with hosting such events. Various licenses or permissions may need to be obtained for live performances and uses of sound recordings, videos, photos, and other intellectual property. This is true for uses both at the event as well as before and after. Get them in writing and get them ahead of time!

- It is best to seek fiscal sponsorship for your fundraising efforts. Not only will you benefit from the sponsors capabilities and support, but fundraising without a fiscal sponsor may cause you to incur a large personal tax bill for your fundraising efforts.

- In spite everything above, don’t be discourage. You’re doing awesome work for people in need.

And now for the details…

Your Place or Mine? Issues with Venue

So you have decided that you want to throw a charitable event. For most organizers, the first choice to be made is where to host the event. Naturally, your choices are likely to be an existing venue or alternatively, creating your own performance space a la an outdoor festival. Arguably, is often easier to host the event at an existing venue for obvious reasons that include (1) the preexistence of event infrastructure (including sound, light, and video equipment, bathrooms, food/drink capabilities, etc.) at no additional cost, (2) a highly-trained staff that is accustomed to dealing with such events and (3) the existence of the all-important licenses to serve food and alcohol. Additionally, in the event musical public performance licenses are required (see below), the venue may already have those in place as well. However, if hosting your event at an established venue is impracticable or not desired, there is always the option creating your own space. But be aware that creating temporary public performances spaces comes with a host of additional considerations and requirements. Failing to adhere to them could get the plug pulled on the event or worse, expose you to serious legal trouble.

Specifically, most jurisdictions will have detailed permitting requirements to host outdoor entertainment events that may include the satisfaction or payment of an application fee, site fee, security deposit, staff costs, city services cost, and insurance indemnification. For example, here in Philadelphia, there are no less than six city departments that may need to sign off on an application prior to issuance of a event permit, each with their own unique requirements including the possibility of additional permits beyond the initial event permit. Want to serve food? Yeah, that’s another permit. Alcohol? Still another. How about a large tent, canopy, or stage setup? You guessed it, one more. Expecting a large crowd? You might be required to have paid-security/police to staff the event. Oh, and let’s not forget those pesky noise ordnances either. I’m sure by now, you get the point. While not insurmountable, creating your own performance space requires comporting with a host of applicable legal requirements and ordinances that can prove daunting on well-meaning but inexperienced event organizers.

We’re Gathering for a Good Cause, What Could Possibly Go Wrong? Issues with Liability

So you got the permit and now you are ready to rock. Not so fast. Though it would seem obvious enough, any time the public is invited to large gatherings, the potential for liability is great. Whether it is an unexpected weather event, negligence on behalf of participants, or any number of other unanticipated causes, event organizers must be proactive in risk planning. It is incumbent on organizers that they discuss, document, and disseminate formal risk mitigation strategies such as evacuation plans, warning signs, availability of first-aid and first-responders, and any other steps that may be necessary to maintain safety for everyone involved.

To Organize or Not?

In the unfortunate event of injury, damage, or loss, organizers risk being held liable, maybe even personally. Because of that, if a limited-liability entity such as an LLC or corporation is available to formally helm the event, it should be used. However, if no such entity exists, and given that most charitable events are likely to be one-offs, the decision to formally organize must be carefully considered. On the one hand, barring exceptional circumstances such as gross negligence or a violation of fiduciary duties owed to the organization, a limited-liability entity would usually insulate the organizers from personal liability. Also, there may be additional tax benefits realized through formal organization. On the other-hand, the formalities and additional reporting requirements, when viewed in light of the attendant risks and combined with insurance coverage, may or may not justify the cost and time associated with formally organizing. Of course, risk is often commensurate with size and scope, and if in doubt, it is best to consult with an experienced attorney to discuss the issue.

Just In Case: Issues with Insurances

Regardless of the decision to formally organize, and regardless of where you choose to host your event, it is always a good idea…and as indicated above, often a requirement…to carry event insurance. The type and amount of insurance will vary depending on your specific circumstances. For most small events, general event liability may suffice. But for larger events or events with peculiar aspects, additional forms of insurance may be prudent or required such as property & equipment, product liability, transit, income protection, directors & officers, workers compensation, volunteers, professional indemnity, non-appearance, cancellation and abandonment. Although insurance is a cost that will ultimately cut into the total amount raised, it is far better to be out a little bit of money upfront and have the protection in place than to not have coverage at all, be sued, and risk losing all of the money you worked so hard to garner for a good cause.

We’re Cool, But We’re not THAT Cool. Issues with Intellectual Property.

An easily-overlooked aspect to charitable events are the intellectual property considerations. Often, organizers are unaware that such issues exist or simply make the mistake of assuming that because there is a beneficial purpose behind the event, they are excused from securing the usual rights needed for public performance, reproductions, distribution, use of image and likeness, and so on.

Public Performance

Assuming that you will have music performed at the event, be it by a live band or by a DJ, you as the event organizer are responsible for ensuring that any required ‘public performance licenses’ are in place. A public performance license is required any time a musical work is performed “at a place open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered.” Clearly, this will include most benefit events. And while there is a limited exception to the requirement of a public performance license for “charitable purposes”, such an exception does not apply to events that “directly or indirectly” charge for admission, nor any event that pays its performers, promoters, or organizers. Though it is likely that most organizers and performers at charitable events will participate without compensation, this will still rule out events seeking to raise money through tickets (direct) or ‘required donations’ (indirect).

If hosting at a venue, check with the venue to ensure it has secured the appropriate licenses. If it has not, or you are creating your own space, most public performance licenses you will need can be obtained through the three major American performing rights organizations: BMI, ASCAP, and SESAC.

Image & Likeness

You are obviously going to want to promote your event diligently to have the highest impact possible. Maybe you’re entertaining flyers, social promotions, print ads, or even television spots. Whatever the case may be, it only makes sense that you will want to include the names, pictures, and/or stock footage of those performing. Though most artists would jump at the opportunity for such free promotion, you should nonetheless be sure to obtain releases from all participant giving you permission to use their ‘image and likeness’ for promotional purposes. Additionally, you will want to ensure that the specific photo or video you are using is not owned by a third-party such as a photographer or videographer. As discussed below, a similar release will be needed if you plan on releasing recordings of the event. If the performer is unable to provide you with such a release or grant of rights, possibly because of prior contractual obligations, ask them who you should contact to secure permission for such uses and be sure to do so ahead of time.

Recordings

In an effort to maximize fundraising, many organizers will seek to record the event for a later demonstration or sale in audio or video format, or both. However, keep in mind that such efforts may require securing additional permissions or licenses from the rights holders separate and apart from the public performance license described earlier. Examples of such licenses may include a synchronization license, master-use license, and as indicated previously, an imagine-and-likeness release. Which licenses you will need necessarily depends what you are releasing, which format(s) you are looking to release in, and who controls the copyrights to the songs or services of the performer. Each situation is case-specific and again, if in doubt, you should consult a music attorney. Regardless, always be clear with the rights owner about exactly what you plan on doing with the final product. In turn, any grant of rights you do obtain should reflect precisely what was discussed and should be secured in writing and prior to the use or dissemination of the product. This will help to avoid any unwanted legal surprises after the fact.

Back In The Real World….

A moment of practicality. Back in the real world, practically speaking, the question of whether a copyright owner would actually bring a suit against a well-meaning organizer who failed to secure such rights is anyone’s guess. It certainly seems less likely than in a for-profit situation, particularly when the money generated is minimal and for the benefit of people in serious need. However, even in times of need, creatives maintain the right to be credited and compensated. Never, never, never (did I make myself clear? Never…) make the assumption they will not make a claim simply because your heart is pure. As the saying goes, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of recovery. Be safe, secure the rights.

Buyer Beware: Fiscal Sponsorship & Tax Issues

Grab a drink and hold on, we saved the best for last. You worked your butt off to organize your charitable event and low and behold, hallelujah! it turned out it was a smashing success. As a matter of fact, you raised more money than you could ever have imagined possible. And on that proud day, you walked into your favorite charity and handed them a check written from your personal account with quite a few zeros at the end of it. In turn, they hand you back a shiny charitable contribution receipt and one hell of smile. Feels good doesn’t it? You think to yourself, ‘not bad for a kid from Muskogee.’ That is, until a few months go by and suddenly one-day you get a love letter from the IRS saying ‘Good work Champ. Now pay up, you owe us some dough’. And you think to yourself, how can that be? Here’s how…

From a tax-treatment perspective, there are essentially two ways in which individuals or collectives who seek to raise charitable funds can operate: either as a wholly independent entity, or alternatively, as an agent of a charity under the banner of what is known as a ‘fiscal sponsorship’. Of course, to be independent simply means the organizer conducts their activities on their own accord and then donates the proceeds to the charity after-the-fact. Alternatively, in a fiscal sponsorship, the organizer seeks out (what is akin to) an official endorsement of its activities from a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) charitable organization prior to conducting them. While volumes have been written on this subject alone, in short, fiscal sponsorship provides significant tax advantages to the organizer by cloaking its activities in the sponsor’s tax-exempt status, therefore, shielding the organizer from having to pay income tax on the money raised. In exchange for such protections, the sponsoring charity maintains general supervision and control over the organizers fundraising activities. This is different from the independent entity situation described above wherein the organizer controls the flow of money up until the point of donation. It is this distinction in control that makes a difference in the eyes of the IRS. According to Professors Cheryl Metrejean and Dr. Britton McKay of Georgia Southern University’s School of Accountancy,

“The specific tax consequences of a benefit concert to the performer will depend on the circumstances surrounding the event. However, in general, if the performer does not form a charitable organization or partner with an existing organization, the income from the event will likely be taxable to the performers. All reasonable expenses paid from the proceeds would be deductible. In addition, the amount donated as a qualified charitable contribution is deductible but the deduction may be limited based on income.”

In other words, operating outside the umbrella protections of charitable status can cause the after-expense proceeds to be viewed as income TO YOU! Still further, even if you subsequently donate 100% of those after-expense proceeds to your cause de jour, you will still only be able to claim an income-offsetting deduction if (1) it’s received by a bona fide 501(c)(3) charity and (2) you itemize your year-end deductions. Provided those criteria are met, the total annual deduction amount still cannot exceed 50% of your adjusted gross income (AGI) for the year in which you take it. What???

Perhaps A (Very Dumbed Down) Comparative Example Will Help…

John, a hard-working singer-songwriter, rounds up the best and brightest regional talent and throws a very successful fundraiser for the victims of Hurricane Harvey. The event generates $17,500 after expenses. John, who himself only made $12,000 last year, subsequently forwards all $17,500 to the Grammy Foundation’s MusicCares Hurricane Relief Fund. Let’s see what happens both with and without a fiscal sponsor.

Scenario#1: Without a Fiscal Sponsor

Under current IRS rules, the $17,500 is treated as income to John and now, instead of $12,000, John is showing $29,500 in income for the year. As such, that income may only be offset by claiming either the standard deduction or itemizing deductions, but not both. Because the standard deduction for individuals in 2017 is only $6,350, John opts to take the itemized deduction. We assume for simplicity sake John has no additional itemized deductions. Under the 50% of AGI limitations, John can only reduce his income up to amount of $14,750 (or 50% of $29,500) which leaves him with taxable base of $14,750. We further reduce that amount by the standard personal exemption of $4050, leaving him with final taxable amount of $10,700. Based on the applicable 2017 tax tables, that equals a tax bill of $1138.

Scenario#2: With a Fiscal Sponsor

As an agent of the charity, the $17,500 is treated as having been directly generated by the charity and will have no bearing on John’s income for the year. Thus, John’s year-end tax base will start at the lower amount of $12,000 and be further reduced by two entitlements; the standard deduction of $6,350 and a personal exemption of $4050, leaving him with taxable income of $1600. Again, using the 2017 tax tables, this equates to a tax bill of $160, a difference of $978 in taxes owed. Geez, that’s some reward for all of your hard work!

As you can see, operating without a fiscal sponsor can have a significant tax impact on the organizer(s). While the above examples are extremely simplified versions of otherwise complicated real-world scenarios, it begs the point that one must be careful when operating in his or her personal capacity as a fundraiser. Similar to the infringement discussion above, whether or not the IRS would actually forego enforcement of its own rules (… I’m looking at you Lucky Homerun Ball Boy).. against a well-meaning fundraiser in such a scenario should never be assumed.

As always, you should discuss the particulars of your situation with a professional tax adviser.

The Last Word… Do Not be Discouraged!

If after reading this article, you feel like heading for the hills, I’m here to tell you, don’t! It is merely a cautionary heads-up. You’re doing amazing work that is desperately needed. With just a little bit of planning and foresight, you can both protect yourself and have a successful event. As always, you should consult professionals in the respective fields for further guidance. Many will be happy to help at little to no cost. Additionally, there are many great organizations such as your local Volunteer Lawyers for The Arts, Fractured Atlas, and the National Network of Fiscal Sponsors to turn to for additional guidance.

This article is for informational purposes only and not intended as legal or tax advice. As always an attorney and/or an accountant specializing in the field should be consulted personally.

(Photo by Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez, SC National Guard (170831-Z-AH923-039) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)